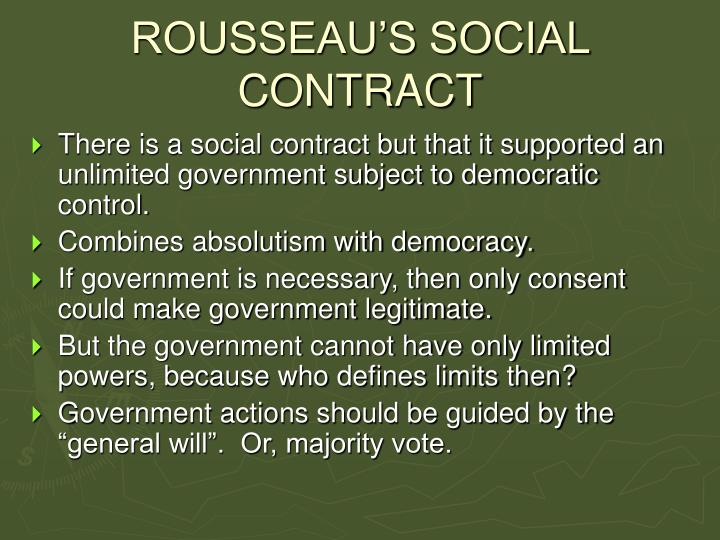

Another clause that ensures legitimate, political authority holds that the law can only deal with matters that affect the entire populace. Because a contract creates obligations for both parties, the people would no longer be the supreme authority if they had to obey the government. To ensure that the people only obey themselves, the sovereign must be the supreme authority in the state. Rousseau claims that there is no contract between the people and its government. To meet these two conditions, Rousseau creates several rules for the sovereign and the government that must carry out its decisions. Second, by obeying the laws, the people only obey themselves. First, there are no relationships of particular dependence. In Book I, Rousseau establishes two conditions for a legitimate polity. Sovereignty is also indivisible, because a part of the sovereign cannot legislate for the whole.

Thus, sovereignty cannot be transferred to an individual or group, because only the people can express the general will. The sovereign must also ensure that the people obey only themselves and remain as free as they were prior to the institution of the social contract. It can only consider matters that affect the entire populace, and cannot demand more from any one subject than from any other. The sovereign must maintain equality, without which liberty cannot exist.

Rousseau places several stipulations on the sovereign to ensure the legitimacy of political authority. Every person is both a "citizen" (in that he is a member of the sovereign) and a "subject" (in that he must obey its decisions).

By banding together, the people create a "public person" called the "sovereign," which aims for the common good. Unlike Hobbes and Grotius, Rousseau asserts that the people should exercise sovereignty rather than bend to the whims of an absolute monarch. Rousseau's theory of sovereignty differs dramatically from those espoused by other political philosophers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)